Six lives lost in Dresden

April 28 is Canada's Day of Mourning for workers killed on the job

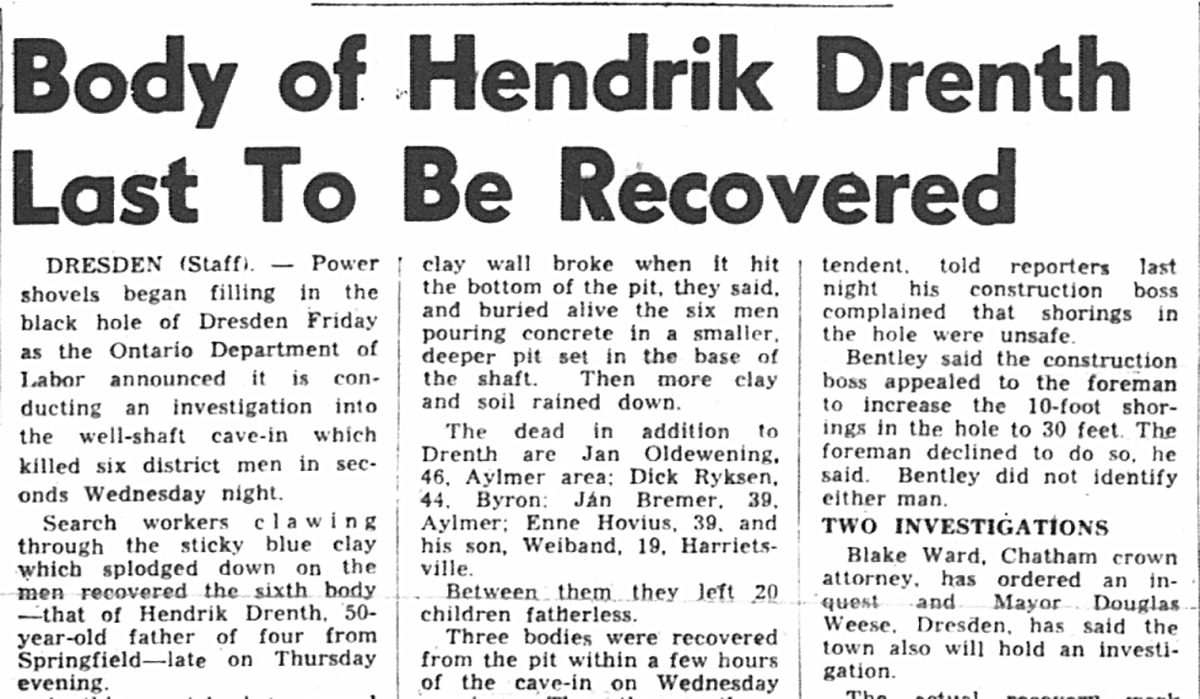

On August 14, 1957, the east wall of the pit they were working in collapsed. Five workers were buried alive, almost instantly. Their foreman was standing on the lower edge of excavation and either jumped in to try to rescue them, or was thrown in by the force of the collapse. A second wave of earth and clay followed immediately and he, too, was killed. The cave-in happened at 7pm. The men had been working in the pit all day and had almost finished pouring the last load of concrete.

Today, on April 28, Canada's Day of Mourning for workers killed on the job, we remember these men.

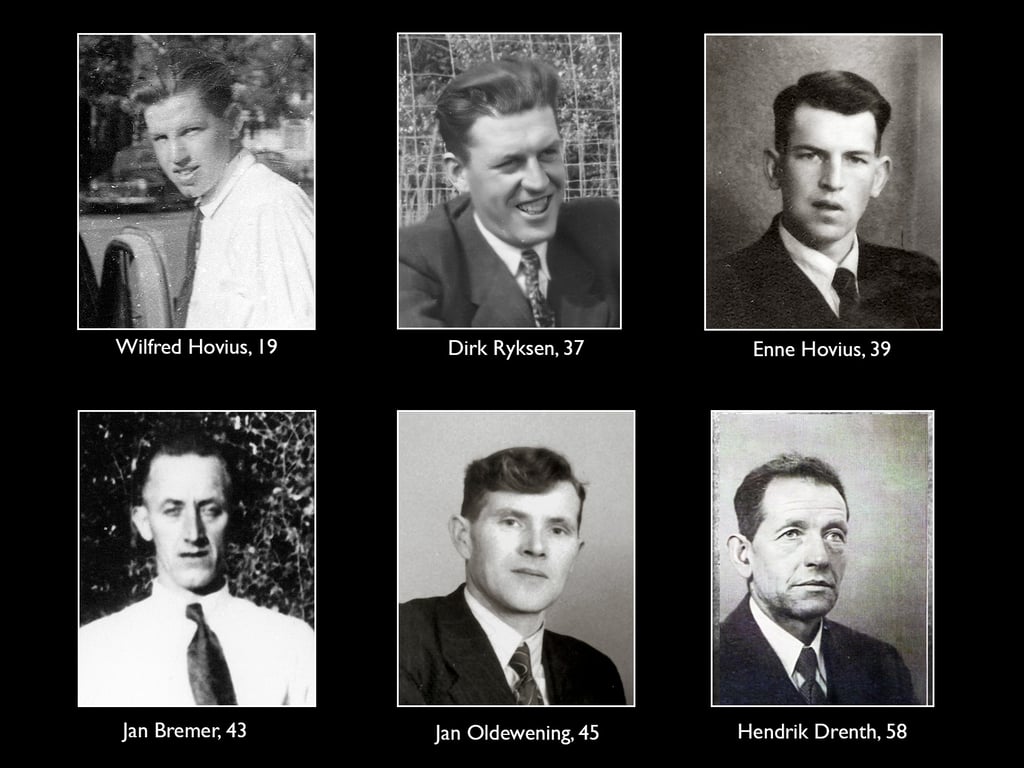

All six of the victims had arrived in Canada with their families between 1950 and 1953. The youngest was Wilfred Hovius (19), who died with his father Enne (39). The Hovius family emigrated from Grijpskerk, near Groningen in the north part of the Netherlands and landed at Pier 21 in Halifax on May 16 in 1953. They first settled in the Cornwall area, and moved to Aylmer two years after that.

The Hovius family with Enne (left), and Wilfred (middle) Dutch families often had formal photos taken before emigrating.

Wilfred was a bright young man, liked and admired by his peers. Although he was an excellent student, like so many Dutch immigrant children in the 1950's, he had to leave school to help support the family. Earlier that summer, he'd travelled to Michigan with his friend Andy Hiemstra. Working in Dresden he spent his spare time with Harry Okkema, who was also 19.

Enne Hovius was a self-employed farm labourer, government inspector and dairy farmer. His dream was to own his own diary farm, but he felt this would only happen if he emigrated. While employment in Canada had been sporadic, he and his family were saving up for the downpayment on a farm near Aylmer. Enne knew that the job in Dresden was dangerous, but he needed the work. Before leaving for work that week he told his wife, "if something happens, you have John." John Hovius, who was just 13 at the time, heard his father say those words.

Wilfred with a friend in Michigan, earlier in the summer of 1957.

The oldest victim, Hendrik Drenth, was 58 when he died. Henrik's body was the last one recovered, nearly 38 hours after the cave-in. Hendrik and his wife Harmke came to Canada with their five children in 1950. Dutch immigrants at that time were required to spend their first year in Canada working for a farmer sponsor, and the Drenth's sponsor was an unkind man and a drinker. It got so bad that the family secretly packed up their entire household and left one night under cover of darkness.

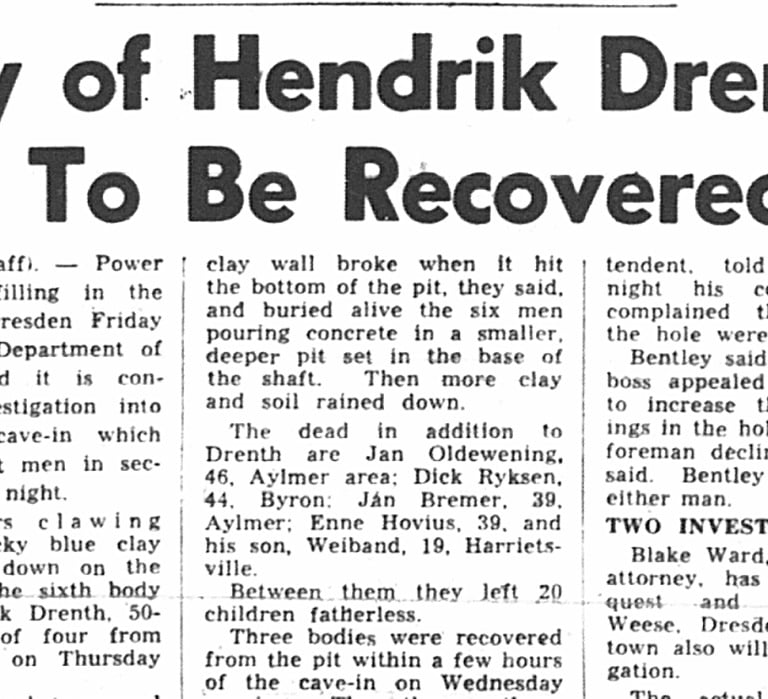

An article from the St. Thomas Times-Journal. As with other articles, the ages given for the men weren't always correct. A quote from Douglas Bentley at Keillor Construction attempts to pin the blame for the cave-in on the foreman.

Jan Bremer emigrated with his family in 1951, first settling in Alberta. Hearing that there was more work in Ontario, he decided to move. But it turned out that his eldest daughter, Jane, had fallen in love with another Dutch immigrant called Dave DeVries. So, with a new son-in-law in tow, they moved to Aylmer. Jan had three daughters and and adult son, and was just 43 when he died

Jan Bremer (right) with his family after moving to Canada.

Jan Oldewening and his wife came to Canada with their four children in 1953. Jan had been in the Dutch army before the German occupation in 1940. He was a skilled tradesmen and, after his obligatory year working on a farm, was able to find employment in construction. A few months before he died Jan was hospitalized with stomach ulcers. Having the same blood type, his wife gave transfusions directly from her arm into his in the hospital, which helped save money.

Jan Oldewening at the outbreak of the Second World War. The Netherlands was occupied for over four years.

Dirk Ryksen was a young and energetic foreman for Keillor Construction. He emigrated from the Netherlands with his wife Margaretha in 1950. Since they didn't yet have children, they worked together on tobacco farms and built their own house, which is still standing today in the London suburb of Byron. Their son John was born in Canada.

Dirk and Gretha Ryksen during their first years in Canada.

Before the job in Dresden, Dirk had worked with a large crew of Dutch immigrants building the Highway 73 bridge over the new 401 highway. All five of the other men had been in that crew.

Dirk was just 37 when he died. Margaretha was determined to stay in Canada, where her husband was buried. She got her Canadian citizenship and found jobs cleaning homes to make ends meet. But, with a young son to care for, the task proved too much. After four years she returned to the Netherlands, where her son John still lives today.

Funeral in Aylmer

On Saturday, August 17, 1957, a mass funeral was held at the Christian Reformed Church in Aylmer. The church was overflowing with mourners and some had to stand outside. At the back of the church, there was a line of six coffins. In the front sat five widows and their 20 children.

Afterwards, a line of hearses pulled up one-by-one, as each coffin was carried out of the church. Five hearses, followed by a procession of cars, drove down highway 73 to the Aylmer Cemetery. There, everyone gathered in a large circle around five freshly dug graves. After the internment ceremony in Aylmer, Dirk Ryksen's coffin was taken to Woodland Cemetery in London, to be buried near where his wife and son lived.

Although they said their goodbyes on that sad day, the tragedy lives on for the families and friends of the men who died. Today, on Canada's Day of Mourning for workers killed or injured on the job, we can remember them.

The five Aylmer-area men are buried side-by-side in the Aylmer Cemetery.

Interested in supporting this documentary film project? Contact us to learn more.