Lest We Forget: The Canadian Liberation of the Netherlands

The DRESDEN 1957 story begins with Canada's role in WWII

Jan Oldewening served in the Dutch army, which fought the invading German army for five days in May 1940

Growing up, memories of the war were a constant presence in my life. My English grandfather was a 17-year-old machine gunner in WWII. He was in France for just two weeks, but that’s all he ever told me.

My Dutch grandfather was a junior communications officer at the time of the German invasion of Holland. Rotterdam, where my mother’s family lived, was the scene of fierce fighting for a few days before the Netherlands surrendered. Since my grandfather knew the city, he was attached to Dutch high command and had a bird’s-eye view of everything.

As a child, I heard the stories of my parents’ wartime experiences: my father grew up in the southeast corner of London, where his family survived the Blitz. My mother lived through the Nazi occupation.

I knew, from my Dutch family, that it was the Canadians who liberated the Netherlands, but I thought they had just kind of marched in at the end of the war. I didn’t realize until much later that Canadian soldiers fought hard for eight long months to free the country.

It started in the south, with efforts to free the Scheldt estuary, which would allow the Allies to bring supplies into the port city of Antwerp— which, like Rotterdam, is actually some distance inland from the coast. The Scheldt was the first piece of the Netherlands to be liberated in the fall of 1944, at the cost of over 6,000 Canadian lives.

During the winter of 1944-45, the Canadians held on to the southern edge of the Netherlands with Nijmegen as their furthest point. Not far from there, on the German-occupied side, is Wageningen, where Dirk Rijksen grew up.

Dirk Rijksen in 1950, his first year in Canada. Is he wearing part of an old army uniform?

The Canadians held the line there, while the Americans to their south fought back a surprise German attack known as the Battle of the Bulge.

As the Allies began to cross the Rhine into Germany, surprisingly, the Nazi forces in Holland kept fighting. In March, as the weather started to improve, the Canadians began to work their way up the east side of Holland towards the northern provinces of Drenthe, Groningen, and Friesland, where the other families in the Dresden 1957 story lived

Meanwhile, the big cities of Amsterdam, Rotterdam, and The Hague remained under German control, and the population was starving. Around 20,000 people died in that winter.

As the Canadian army progressed, they brought food and freedom to the Dutch. Food was even dropped by parachute into the big cities. My mother remembers that, and somewhere in our family, we still have a canvas sack that was once filled with life-saving food for starving Dutch civilians.

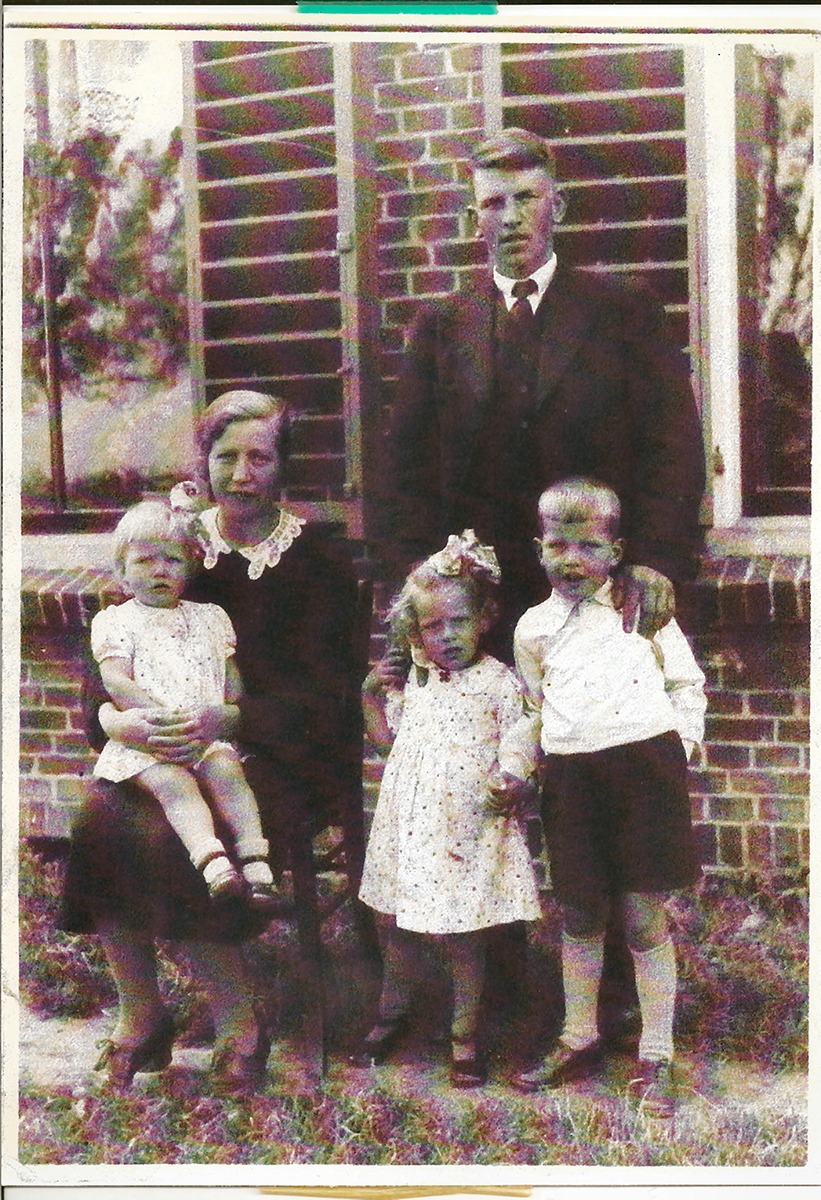

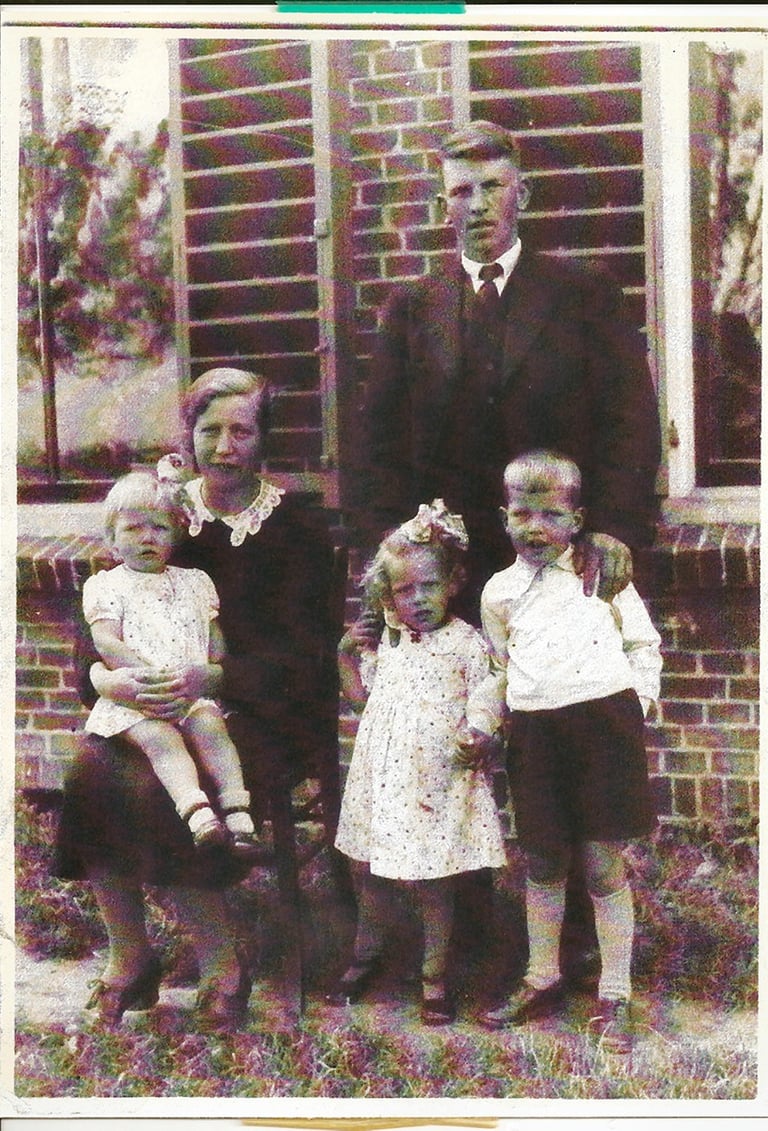

The Hovius family around the time of the war's end.

The fight to liberate the Netherlands reached a climax with the siege of Groningen, which the Nazis had fortified. The defenders included Dutch SS soldiers, men who had joined the Nazis, who probably felt they had nothing left to lose.

The German forces in the Netherlands finally surrendered on May 5, 1945, just two days before the war in Europe ended.

Allied warplanes brought food and hope to the Dutch cities, including Rotterdam, where my mother's family lived.

All told, over 7,600 Canadians gave their lives to liberate the Netherlands, most of whom are buried today in well-tended cemeteries in that country.

The Dutch have never forgotten, and neither should we.

Jubilant crowds greet the Canadian forces after the liberation of Arnhem in 1945.

The Dresden 1957 story has its beginnings in this story of sacrifice. The bonds forged between Canada and the Netherlands were the reason so many Dutch immigrants came to Canada in those difficult postwar years. Among them were the Bremer, Drenth, Hovius, Oldewening, and Rijksen families.

Learn more about our documentary project on this site and this blog. To support our initiative, make a contribution on our crowdfunding page.